George Scicluna

George Scicluna

It is a certain sustained softness and tenderness in curvaceous melted forms, with a constant rhythm of globular modules, that form spherical shapes in infinite movement that immediately strikes you. The serenity, tranquillity and harmonious sense these works exude expose the sublime and classical in an expressive artist who struggles to keep still in his tormented search for solutions to problems that are beyond human ken. His persistent exploration and search for answers to vital questions, his leap into the unknown, his dissatisfaction at failure to comprehend fully is reflected in his work, as in art like life we are always alone and there are no answers. This struggle in his search surfaces in some of these works too when resolution gives way to anguish and torment as the melted forms intertwine, interlink or become entangled and enmeshed.

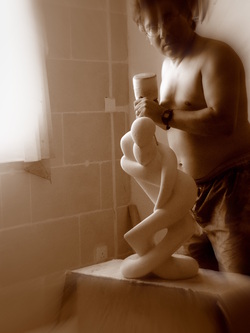

George Scicluna (1966- ) has finally decided to exhibit a collection of 25 works in sculpture. His chosen medium is soft globigerina limestone or ‘franka’. Without doubt this material has several advantages or properties. The craft is as old as prehistoric man, hewn effortlessly, has a rich honey-coloured hue, weathers beautifully and with time it develops a patina that seals and protects it. Since it is like cutting into butter or cheese it can be shaped beautifully, and using abrasives it can easily be smoothened into round and curvaceous forms of great purity, simplicity and refinement by a sensitive and sensible artist. But unlike hard stone the artist cannot use force to tame it into submission. He has to be tender and kind.

George must have contained himself as an expressive artist of passion, power and struggle. With ‘franka’ he had to be gentle and considerate. What is amazing is the suggestion of pain and suffering he suggests with wringing and rinsing movement of shapes and forms as they become interlocked, entangled and enmeshed. Perhaps even in a state of serenity and tranquillity George perceives struggle and discord. Yet the harmony, peace and silence this collection evokes are incredibly suggestive.

‘Pregnant Mother’ in its melted and distorted form is quite surreal and perhaps the tenderness and softness of its shapes do not detract from the overall sense of tragic drama in its contorted and convoluted form that implicitly suggest pain and suffering. Even ‘Contortionist’ is eloquently surreal in its Dalí-like convolutions. While ‘Entangled’ has a deeper meaning than mere ‘oneness’. The unity in the knotted form could imply tension though the stress is resolved.

George was born and nurtured in Rabat, Victoria Gozo surrounded by rounded hills and rolling countryside. The curvaceous breast-like hills were perhaps his first inspiration; the megalithic site of ‘Ġgantija’must have impressed itself on his memory and he could hardly have escaped the influence left by Henry Moore (1898-1986) whose drawings were exhibited in Malta (1). Also of a relative importance is the tradition in stone sculpture practised by George’s friend Joe Xuereb (1954- ) of Għajnsielem, Gozo (2). It seems there is a certain affinity between their work though since there is a marked difference in temperament and vision the similarity stops there.

The reference to Henry Mooore could be misleading. Though Henry Moore was quite versant in medieval art, in primitive, elemental and simple forms, George’s work leans more towards the rounded, smooth forms of Romanian sculptor Constantine Brâncuşi (1876-1957) and Jean Arp (1886-1966) from Alasace (who both influenced Moore) and the metaphysical, rounded mannequin heads of Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) and the dream-like surrealism of Salvador Dalí (1904-1989).

Yet Moore’s Italian influence of the masters namely: Giovanni Pisano, Giotto, Masaccio and Michelangelo go down well with George’s leaning and obsessions. More important though is Mooore’s influence by Tino di Camaino (c.1280-c.1337) and Arnolfio di Cambio’s (c.1240-c.1302) works in the Opera del Duomo Museum in Florence since the sculptor lived on the pheriphery of the city and studied their frontal and medieval forms at length. The subjects tackled by George: maternity and the family are those that Moore frequently used of the seated, frontal figures of a ‘Madonna Enthroned’ by Arnolfo di Cambio (Virgin and Child, c.1296-1302, marble, h. 174cm, Museo del Opera del Duomo). There is the tomb of ‘Bishop Orso’ (after 1320,marble, h.132cm) and a related ‘Enthroned Madonna’ (c.1320, marble, h. cm78) that probably acted as a finiale that are related to bold seated forms with protruding open knees that prop falling folds. Though these forms serve to inspire Moore’s and George’s subjects, the smoothness and vitality of the basic forms are derived from ‘Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany 1’ (1912, white marble on limestone block, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia) exhibited at the 1913 armory Show and ‘Sleeping Muse’ (1910, bronze, 17x24x15cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) by Costantine Brâncuşi.

‘Homage to Arp’ is mostly related to this sculptor’s work as he was also much admired by Moore together with a group of masters including Picasso, Braque and Giacometti that the sculptor and Hepworth and artists from the group ‘Seven & Five Society’ frequently visited in Paris when Henry was Head of Department of Chelsea School of Art around 1932. In ‘Contortionist’ George shows great admiration of Salvador Dalí’s metaphysical surrealism that Giorgio de Chirico practised too. But the melting form is purely an echo of Dalí.

In ‘Entangled’ and ‘Movement’ George leaves no doubt that his sculpture evolves from his painting. George interprets materpieces in painting by his favourite chords and arcs forming votices and vibrant circular movement. He does the same in his sculpture at times achieving similar composition as ‘Morose’ and ‘Penseroso’ where the votices suggest sadness and meditation. In ‘Embrace’ George echoes his well know painted work: ‘In Memory after Francis Bacon’ whose figure is entwined with that of his partner George Dyer. ‘Union’ is reminiscent of ‘Adam and Eve’ a painting that projects the union of man and woman as ‘ two in one and one in two’.

‘George believes that the movement of man resembles that of a wave: it is basically circular, oscillatory. He works in vortices. He is the eye of the storm. Where he stands is resolution. The energy springs from his hand in centrifugal force’. (3) Where the viewer stands is chaos but George invites him to an enclave of silence and peace.

‘Art is the lie that tells the truth’, Pablo Picasso maintained. For George Scicluna the only reality is the creative act.

E. V. Borg - March 2013

(1) Henry Moore’s exhibition in Malta (has to search for details)

(2) Borg. E. V. ‘Form in Stone – Joe Xuereb (1954- ), In Malta This Month, Air Malta In-Flight Magazine, no. 52, July 1994 (author’s no. 48)

(3) Borg E. V. ‘A Divine Struggle’, catalogue Essay, 1998.

It is a certain sustained softness and tenderness in curvaceous melted forms, with a constant rhythm of globular modules, that form spherical shapes in infinite movement that immediately strikes you. The serenity, tranquillity and harmonious sense these works exude expose the sublime and classical in an expressive artist who struggles to keep still in his tormented search for solutions to problems that are beyond human ken. His persistent exploration and search for answers to vital questions, his leap into the unknown, his dissatisfaction at failure to comprehend fully is reflected in his work, as in art like life we are always alone and there are no answers. This struggle in his search surfaces in some of these works too when resolution gives way to anguish and torment as the melted forms intertwine, interlink or become entangled and enmeshed.

George Scicluna (1966- ) has finally decided to exhibit a collection of 25 works in sculpture. His chosen medium is soft globigerina limestone or ‘franka’. Without doubt this material has several advantages or properties. The craft is as old as prehistoric man, hewn effortlessly, has a rich honey-coloured hue, weathers beautifully and with time it develops a patina that seals and protects it. Since it is like cutting into butter or cheese it can be shaped beautifully, and using abrasives it can easily be smoothened into round and curvaceous forms of great purity, simplicity and refinement by a sensitive and sensible artist. But unlike hard stone the artist cannot use force to tame it into submission. He has to be tender and kind.

George must have contained himself as an expressive artist of passion, power and struggle. With ‘franka’ he had to be gentle and considerate. What is amazing is the suggestion of pain and suffering he suggests with wringing and rinsing movement of shapes and forms as they become interlocked, entangled and enmeshed. Perhaps even in a state of serenity and tranquillity George perceives struggle and discord. Yet the harmony, peace and silence this collection evokes are incredibly suggestive.

‘Pregnant Mother’ in its melted and distorted form is quite surreal and perhaps the tenderness and softness of its shapes do not detract from the overall sense of tragic drama in its contorted and convoluted form that implicitly suggest pain and suffering. Even ‘Contortionist’ is eloquently surreal in its Dalí-like convolutions. While ‘Entangled’ has a deeper meaning than mere ‘oneness’. The unity in the knotted form could imply tension though the stress is resolved.

George was born and nurtured in Rabat, Victoria Gozo surrounded by rounded hills and rolling countryside. The curvaceous breast-like hills were perhaps his first inspiration; the megalithic site of ‘Ġgantija’must have impressed itself on his memory and he could hardly have escaped the influence left by Henry Moore (1898-1986) whose drawings were exhibited in Malta (1). Also of a relative importance is the tradition in stone sculpture practised by George’s friend Joe Xuereb (1954- ) of Għajnsielem, Gozo (2). It seems there is a certain affinity between their work though since there is a marked difference in temperament and vision the similarity stops there.

The reference to Henry Mooore could be misleading. Though Henry Moore was quite versant in medieval art, in primitive, elemental and simple forms, George’s work leans more towards the rounded, smooth forms of Romanian sculptor Constantine Brâncuşi (1876-1957) and Jean Arp (1886-1966) from Alasace (who both influenced Moore) and the metaphysical, rounded mannequin heads of Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) and the dream-like surrealism of Salvador Dalí (1904-1989).

Yet Moore’s Italian influence of the masters namely: Giovanni Pisano, Giotto, Masaccio and Michelangelo go down well with George’s leaning and obsessions. More important though is Mooore’s influence by Tino di Camaino (c.1280-c.1337) and Arnolfio di Cambio’s (c.1240-c.1302) works in the Opera del Duomo Museum in Florence since the sculptor lived on the pheriphery of the city and studied their frontal and medieval forms at length. The subjects tackled by George: maternity and the family are those that Moore frequently used of the seated, frontal figures of a ‘Madonna Enthroned’ by Arnolfo di Cambio (Virgin and Child, c.1296-1302, marble, h. 174cm, Museo del Opera del Duomo). There is the tomb of ‘Bishop Orso’ (after 1320,marble, h.132cm) and a related ‘Enthroned Madonna’ (c.1320, marble, h. cm78) that probably acted as a finiale that are related to bold seated forms with protruding open knees that prop falling folds. Though these forms serve to inspire Moore’s and George’s subjects, the smoothness and vitality of the basic forms are derived from ‘Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany 1’ (1912, white marble on limestone block, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia) exhibited at the 1913 armory Show and ‘Sleeping Muse’ (1910, bronze, 17x24x15cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) by Costantine Brâncuşi.

‘Homage to Arp’ is mostly related to this sculptor’s work as he was also much admired by Moore together with a group of masters including Picasso, Braque and Giacometti that the sculptor and Hepworth and artists from the group ‘Seven & Five Society’ frequently visited in Paris when Henry was Head of Department of Chelsea School of Art around 1932. In ‘Contortionist’ George shows great admiration of Salvador Dalí’s metaphysical surrealism that Giorgio de Chirico practised too. But the melting form is purely an echo of Dalí.

In ‘Entangled’ and ‘Movement’ George leaves no doubt that his sculpture evolves from his painting. George interprets materpieces in painting by his favourite chords and arcs forming votices and vibrant circular movement. He does the same in his sculpture at times achieving similar composition as ‘Morose’ and ‘Penseroso’ where the votices suggest sadness and meditation. In ‘Embrace’ George echoes his well know painted work: ‘In Memory after Francis Bacon’ whose figure is entwined with that of his partner George Dyer. ‘Union’ is reminiscent of ‘Adam and Eve’ a painting that projects the union of man and woman as ‘ two in one and one in two’.

‘George believes that the movement of man resembles that of a wave: it is basically circular, oscillatory. He works in vortices. He is the eye of the storm. Where he stands is resolution. The energy springs from his hand in centrifugal force’. (3) Where the viewer stands is chaos but George invites him to an enclave of silence and peace.

‘Art is the lie that tells the truth’, Pablo Picasso maintained. For George Scicluna the only reality is the creative act.

E. V. Borg - March 2013

(1) Henry Moore’s exhibition in Malta (has to search for details)

(2) Borg. E. V. ‘Form in Stone – Joe Xuereb (1954- ), In Malta This Month, Air Malta In-Flight Magazine, no. 52, July 1994 (author’s no. 48)

(3) Borg E. V. ‘A Divine Struggle’, catalogue Essay, 1998.